I’m an impostor. At least, I perceive myself to be: I am a fraud, a know-nothing, a talentless buffoon who wrote a story people liked and have cruised by on their goodwill ever since.

Is this true? Possibly, possibly not. My brain choruses YES at a deafening volume: yes, you’re going to get found out any day now. Your mediocrity is the world’s worst-kept secret. You are the emperor, cavorting naked while everyone politely averts their gaze. (I think I had a nightmare like that once.)

This actually has a name. It’s called ‘Impostor Syndrome‘. It affects all kinds of people, but seems especially prevalent among creative people, and especially prevalent among female creatives. Wikipedia describes it quite succinctly:

Despite external evidence of their competence, those exhibiting the syndrome remain convinced that they are frauds and do not deserve the success they have achieved. Proof of success is dismissed as luck, timing, or as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent and competent than they believe themselves to be

I happened upon this recently, when reading an article about writers & procrastination – frustrated by my own apparent inability, over the course of four days off work, to knuckle down and write more than 300 words in a day. And not only that, but two instances in which I have had ample time to hit a deadline, but have found myself with three weeks to go, frantically bashing out a short story I have had fully-formed in my head for a month or longer. Why do I do this to myself, I wondered? Is it some kind of executive dysfunction, or am I just lazy and badly disciplined?

(Well. I think there is certainly an element of the latter.)

But a quote from the Atlantic article put some things into stark perspective for me:

Most writers manage to get by because, as the deadline creeps closer, their fears of turning in nothing eventually surpasses their fears of turning in something terrible. But I’ve watched a surprising number of young journalists wreck, or nearly wreck, their careers by simply failing to hand in articles. These are all college graduates who can write in complete sentences, so it is not that they are lazy incompetents. Rather, they seem to be paralyzed by the prospect of writing something that isn’t very good.

So far, my fear of disappointing people is winning out over my fear of writing a pile of unreadable garbage. In the war of my many neuroses, I’m treating this as a win.

It strikes me, though, how many people I know who feel the same way, and not just writers but artists, videogame creators, musicians. For every confident, self-assured creative I know there are two more hiding in the corner, tearing their hair out for myriad reasons: other people are making better games than me. Other people’s art is more popular than mine. Other people write faster, better, produce more. Other people’s songs are cleverer, catchier. Or, if comparison isn’t a factor – and it isn’t always: my stories are objectively poor and I’ve just been lucky so far. My art doesn’t look the way I wish it did. Nobody is interested in the game I’m making and therefore it must be awful.

(And yes, I would say that the vast majority of these people happen to be women.)

There are hundreds of reasons for these outcomes, but we see just one: a big red arrow pointing down at us, the creator. The words ‘loser’ may or may not be spray painted on our foreheads. It’s an optional extra. And what’s interesting is how hard we work to negate any successes or kind words that might work to counter our perceptions; it’s as though we have an internal filter sifting out all the gold nuggets and ensuring that our attention is focused solely on the piles of mulch. Who cares that you’ve been published X times, or that a piece of your artwork got thousands of likes/reblogs on Tumblr, or that someone looked at the progress shots of your indie game and said ‘this looks awesome’. Who cares about any of that? It was luck, it was a fluke.And even if it wasn’t – even if that award nomination/sale/good review was legit – it doesn’t matter, because you’ll never produce anything of that quality ever again. The future is one failure after another. You’ll be the literary equivalent of that person who turns up to parties – the one nobody really likes but entertains anyway because they all feel a bit sorry for them. You know the one.

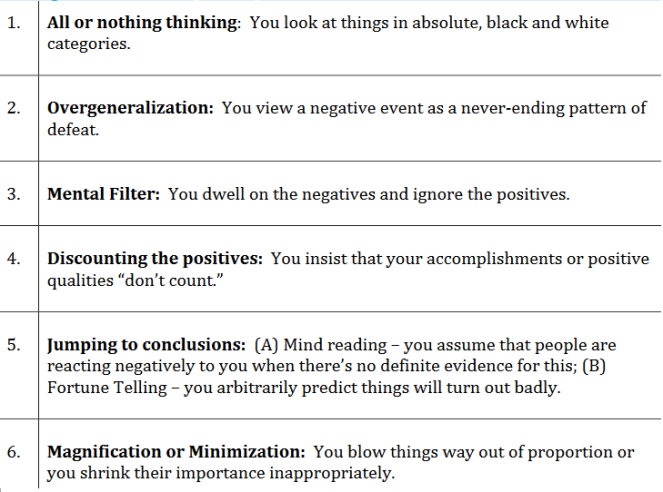

This is cognitive distortion. It’s a form of disordered thinking common in OCD and anxiety disorders (as I learned in therapy) – and when I look at the list of cognitive distortions I come to understand how similar impostor syndrome is to my own diagnosed disorders:

The same lessons I learned in dealing with my anxiety and OCD can be applied to this as well. Disorders which deal in the illogical require proof in retaliation: when we say “I am a bad writer”, we owe it to ourselves to look at all the evidence and come to a balanced conclusion. Instinct and gut feelings are overrated. And the temptation is to say well, it’s difficult to change the way I feel, it won’t happen overnight, I’ve tried before and it didn’t work, but…

The only way to change anything it to make it change, right?

And while we’re talking changing attitudes, consider this: it’s okay to fail. Rejection hurts like hell. A bad review stings. Even being left off a ‘year’s best’ or failing to make an award shortlist can hurt, if that’s what you’re aiming for – or if it happened to you once and it’s never happened since. (“I’m an imposter!” the mind cries. “I’ll never write anything as good as that ever again!”.) And I’m not about to spout some pseudo-philosophical missive about how rejection is actually good for you (although that may be true? Someone more qualified than I am can substantiate.) But to fail isn’t to lose everything. It is literally not the end of the world, even if it feels that way.

Consider that every submission is an act of bravery. Every story you send out for critique. You’re showing your soft underbelly to the world, and who knows what kind of damage they might do? And if you can commit that singular brave act, what else might you be capable of? How can you call yourself an impostor when you are doing the work?

This is a challenge to myself, but also to my fellow impostors. Consider that failure is not the end; it is not proof of anything except that, in this one instance, in that one moment, something just didn’t work out. Failure ought to be a self-limiting phenomenon: it can’t leach out or infect anything else you do. It’s a singular instance, a moment in time. What does failure mean, objectively? Well, worst case scenario dictates it’s that you’re not good enough, but is that realistic? It could be that what you wrote wasn’t right for that publication; that your stories aren’t to that editor’s personal taste. It could be that what you wrote was really very good, it just so happened that someone else’s story was a little bit better (and that’s okay too – I feel like ‘other people are sometimes going to be better than you’ is an important thing to come to terms with as well. Someone else’s talent/hard work doesn’t invalidate your own – success is not a zero-sum game.)

And yes, it could be that what you wrote wasn’t the best example of your work. But that doesn’t prove you’re an impostor. Rather, it’s an incitement to go out and do better next time. Because you can, and because you will.

Because you’re not really an impostor at all. You just think you are.

2 thoughts on “a love letter to impostors everywhere”